1.2 The Evolution of Money: From Barter to Digital

Bartering and Early Exchange

Before money, humans met needs through barter–directly trading goods or services. A farmer might trade a basket of grain for a shoemaker’s pair of shoes. This system works only if both parties have something the other wants. This is the double coincidence of wants problem. Barter is slow and inefficient: if a sword seller meets an elephant hunter, they must negotiate a fair trade or find a third item to balance the exchange. Over time, communities began using easily traded commodities as proto-currencies (such as iron bars, bronze rings, and metal ingots). Early forms of money also included items like animal skins, shells, beads, salt or spices. These commodity monies had some intrinsic value (e.g. salt that preserves food) and were widely accepted, speeding up trade. This step from barter to commodity money was revolutionary: it meant people no longer had to find an exact trading partner each time, greatly increasing the speed and volume of commerce.

Metal Coinage and First Currencies

The emergence of metal coinage marked a transformative chapter in human history, revolutionizing trade, economies, and societies by introducing standardized, durable, and widely accepted forms of money.

The first true coins—small, standardized pieces of metal stamped with symbols to guarantee value—emerged around 700–600 BCE in the Kingdom of Lydia (modern-day western Turkey). These coins, made of electrum (a natural alloy of gold and silver), are widely regarded as the earliest form of coined money. The Lydian king Croesus is often credited with their introduction (though some sources suggest his father, King Alyattes may have initiated their use), leveraging the region's abundant electrum deposits from the Pactolus River. These coins, known as ‘Lydian staters’, bore designs like a lion and bull, symbolizing royal authority, and were valued based on weight and metal purity. Their uniformity and state-backed authenticity reduced disputes over value, replacing earlier ingots or hacksilver (irregular metal pieces weighed per transaction).

This system greatly improved trade as coinage was durable, portable, and divisible (a gold coin could be broken into smaller units), making transactions easier. Entire economies began circulating huge quantities of coins.

Early Development and Spread

The Lydian innovation spread rapidly. By the 6th century BCE, neighboring Greek city-states like Aegina and Athens adopted coinage, using silver mined from local sources. These coins, often stamped with city symbols (e.g. Athens’ owl), facilitated trade across the Mediterranean. In Persia, the Achaemenid Empire introduced the gold daric around 515 BCE, a high-purity coin that became a benchmark for imperial trade. Meanwhile, in China, bronze and copper coins, often with square holes in the center, emerged around the same period during the Zhou dynasty, evolving from earlier knife- and spade-shaped money. India also developed early coinage by the 6th century BCE, with punch-marked silver coins used in the Magadha kingdom, identified by irregular shapes and stamped symbols.

The success of metal coinage stemmed from its intrinsic value (tied to precious metals), durability (unlike perishable commodities), and standardization, which enabled trust across regions. Coins also served as propaganda, bearing rulers’ images or state symbols, reinforcing political authority.

The introduction of metal coinage laid the foundation for modern financial systems, shaping commerce, governance, and cultural exchange across civilizations.

Paper Money and the Gold Standard

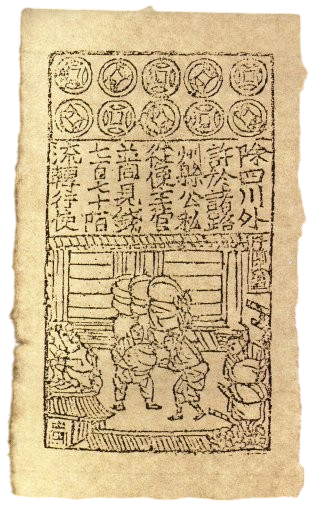

Paper money emerged as a practical solution to the limitations of metal coinage, which was heavy, costly to produce, and prone to clipping or debasement. The earliest forms appeared in China during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) as merchant receipts for deposits of coins or goods, evolving into government-issued notes by the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE). The jiaozi, introduced around 1024 CE in Sichuan, is considered the first true paper money, backed by government reserves and used to pay taxes. By the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368 CE), under Kublai Khan, paper money like the chao became mandatory, supported by silver reserves but often overprinted, leading to inflation.

In Europe, paper money emerged later, driven by similar needs. In the 17th century, Sweden issued the first European paper notes in 1661 through Stockholms Banco, backed by copper and silver but collapsing due to overissuance. By the late 17th century, goldsmiths’ receipts in England acted as promissory notes, exchangeable for gold, laying the groundwork for modern banking. The Bank of England, established in 1694, formalized paper notes, initially as IOUs redeemable in gold or silver. In the Americas, the Massachusetts Bay Colony (an English settlement) issued paper money in 1690 to fund military campaigns, a precursor to colonial currencies.

Rise of the Gold Standard

The gold standard, where currency value is tied to a fixed quantity of gold, emerged to stabilize paper money and curb inflation from overprinting. Its roots trace to the 18th century, but it was formalized in the 19th century. Britain led the way, adopting a de facto gold standard in 1717 under Sir Isaac Newton, master of the Royal Mint, who fixed the pound’s value to gold at £3.17s.10½d per ounce. The Coinage Act of 1816 made gold the sole standard, with silver relegated to subsidiary coinage.

The classical gold standard (1870–1914) marked its global peak, as major economies like the United States, Germany, and France pegged their currencies to gold, facilitating international trade and capital flows. The U.S. formalized its gold standard with the Gold Standard Act of 1900, setting the dollar at $20.67 per ounce of gold. Under this system, paper notes were redeemable for gold, ensuring trust and limiting money supply growth to gold reserves.

Benefits of Paper Money and the Gold Standard

Paper Money: Offered portability and divisibility, unlike heavy coins, enabling complex transactions and large-scale trade. It reduced reliance on scarce metals, with China’s jiaozi facilitating commerce across vast regions. Paper also allowed governments to issue currency for public works or wars, as seen in colonial America.

Gold Standard: Provided price stability, with inflation averaging roughly 1% annually from 1870–1914, fostering trust in paper notes. It enabled international trade by fixing exchange rates, as currencies were valued in gold equivalents, reducing currency risk. The system also disciplined governments, limiting excessive money printing.

Challenges and Instability

Paper Money: Without backing, overissuance led to inflation, as in Yuan dynasty China, where chao notes lost value, or in 18th-century France’s assignats, triggering hyperinflation. Counterfeiting was a persistent issue, requiring watermarks and intricate designs.

Gold Standard: Its rigidity constrained monetary policy, limiting governments’ ability to respond to crises. During World War I (1914–1918), nations suspended gold convertibility to fund war efforts, printing unbacked paper money. Gold supply shortages also restricted money creation, exacerbating deflation, as seen in the U.S. during the 1890s. International imbalances, where gold flowed to surplus nations, strained deficit economies.

Decline of the Gold Standard

The gold standard faltered during the 20th century. The interwar period saw attempts to revive it, but the Great Depression (1929–1939) exposed its flaws, as nations hoarded gold, deepening deflation. In 1933, the U.S. under President Roosevelt banned private gold ownership and devalued the dollar to $35 per ounce, effectively suspending convertibility. The Bretton Woods system (1944–1971) created a modified gold standard, pegging the U.S. dollar to gold and other currencies to the dollar. However, U.S. deficits and gold reserve depletion led President Nixon to end dollar convertibility on August 15, 1971, in the “Nixon Shock,” ushering in the era of fiat currencies.

Transition to Fiat and Legacy

With the gold standard’s collapse, paper money became fiat, backed by government trust rather than metal. This allowed flexible monetary policies but risked inflation, as seen in the 1970s. Today, paper money remains dominant, though digital currencies like Bitcoin, launched in 2009, echo the decentralized ethos of early coinage. The gold standard’s legacy persists in debates over monetary discipline, with some advocating its return to curb inflation, though economists argue it’s impractical in modern economies.

Lasting Impact

Paper money and the gold standard revolutionized global finance. Paper enabled scalable economies, while the gold standard ensured stability during the 19th century’s globalization. Artifacts like Song dynasty jiaozi or 19th-century banknotes, preserved in institutions like the British Museum, highlight their cultural significance. Their principles of trust and standardization continue to shape modern finance, even as digital currencies challenge paper’s dominance.

The Digital Revolution in Finance

The introduction of electronics into finance began in the mid-20th century, marking a shift from manual, paper-based processes to automated systems. By the 1960s, electronic fund transfers (EFTs) emerged, allowing banks to move money between accounts using computer-based systems, significantly reducing processing times compared to manual methods.

Credit cards also transformed consumer spending during this period. The Diners Club card, introduced in 1950, was the first modern credit card, allowing users to make purchases on credit and pay later, initially for dining and travel. By the late 1950s and 1960s, cards like the Bank of America's BankAmericard (later Visa) and MasterCard expanded globally, offering unprecedented convenience and flexibility. Automated Teller Machines (ATMs), first installed by Chemical Bank in New York in 1969, provided 24/7 access to cash, revolutionizing banking accessibility. These innovations made financial services more convenient but relied on centralized banking systems, prompting discussions about access for unbanked populations.

The 1970s and 1990s saw financial systems embrace digital networks, moving away from physical infrastructure. The National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations (NASDAQ), launched in 1971, was the world’s first electronic stock market, replacing physical trading floors with real-time digital transactions. This shift enabled faster, more efficient stock trading, accessible to a broader range of investors.

Similarly, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), established in 1973, revolutionized international money transfers. SWIFT provided a secure messaging system for banks to exchange payment instructions, replacing slower telegraph-based methods with standardized, electronic transfers. By the 1990s, SWIFT handled millions of transactions daily, facilitating global trade and finance. These networks improved efficiency but depended on centralized infrastructure, raising concerns about single points of failure and access in developing regions.

In 1998, PayPal emerged as a pioneering internet payment platform, allowing users to send and receive money online without cash or checks. Initially launched as Confinity, PayPal simplified e-commerce transactions, enabling secure peer-to-peer payments and fuelling the growth of online shopping. Its user-friendly interface and low fees made it a cornerstone of digital finance, though its reliance on internet connectivity highlighted vulnerabilities in network-dependent systems.

The Rise of Mobile Money: Early Foundations (1990s–Early 2000s)

The roots of mobile money trace back to the proliferation of mobile phones in the 1990s, which enabled new communication channels for financial services. In 1999, the Philippines’ Smart Money, launched by Smart Communications, became one of the first mobile payment systems, allowing users to transfer funds via SMS. This early experiment targeted unbanked populations, leveraging basic mobile technology. Similarly, in 2001, Vodafone tested mobile payment services in Europe, laying the groundwork for broader adoption. These efforts were limited by rudimentary phones and lack of infrastructure but demonstrated the potential for mobile-based finance in regions with low banking penetration.

Breakthrough with M-Pesa (2007)

The mobile money revolution gained global prominence with M-Pesa, launched in 2007 by Safaricom in Kenya. Meaning “mobile money” in Swahili, M-Pesa allowed users to deposit, transfer, and withdraw funds using basic mobile phones, even without bank accounts. Backed by Vodafone and funded partly by the UK’s Department for International Development, M-Pesa addressed financial exclusion in East Africa, where only 20% of adults had bank accounts. By 2010, M-Pesa had 9.5 million users in Kenya, handling transactions equivalent to 11% of GDP. Its success spurred similar systems in Africa and Asia, such as bKash in Bangladesh (2011) and EcoCash in Zimbabwe (2011), which provided microfinance and bill payments.

Global Expansion and Smartphone Integration (2010s)

The rise of smartphones in the 2010s accelerated mobile money’s growth. Google Wallet, launched in 2011, introduced NFC-based contactless payments, allowing users to pay with Android devices at compatible terminals. Apple Pay, debuted in 2014, integrated with iPhones, leveraging secure enclaves for card storage and biometric authentication. These platforms, alongside Samsung Pay (2015), popularized mobile payments in developed markets, with global transaction volumes reaching $6.6 trillion by 2021. In parallel, mobile banking apps from fintechs like Chime (2013) and Revolut (2015) offered low-cost accounts, budgeting tools, and international transfers, capturing millions of users.

In developing regions, mobile money continued to thrive. By 2020, Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 70% of global mobile money transactions, with 548 million registered accounts. Services like Airtel Money and MTN Mobile Money expanded across Africa, while India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI), launched in 2016, processed over 100 billion transactions annually by 2025, driven by apps like Paytm and PhonePe.

Current Trends and Future Outlook (2025)

By 2025, mobile money continues to evolve. Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), like China’s digital yuan (2022), integrate with mobile platforms, with over 100 countries exploring similar systems. AI-driven fraud detection and biometric authentication enhance security, while Web3 integrations link mobile money to DeFi platforms. The Global System for Mobile Communications Association (GSMA) predicts mobile money accounts will exceed 1 billion by 2030, driven by 5G and the Internet of Things (IoT) advancements. However, bridging the digital divide and ensuring equitable access remain critical for sustained growth.

As we’ve seen, money has evolved dramatically—from simple barter systems to complex digital networks—each stage designed to make trade more efficient and accessible. But even in its modern form, traditional money isn’t without its flaws. In the next lesson, The Challenges of Traditional Money, we’ll take a closer look at the limitations and systemic issues that continue to affect today’s financial systems, from inflation and centralization to limited access and slow cross-border transactions.