1.4 Economic Crises and Currency Case Studies

The gravity of economic crises is best illustrated by examining real-world financial collapses. Several historical and modern examples highlight what can happen when money systems break down. Here, we look at four notable cases: Weimar Germany (1922–23), Zimbabwe (2007-2009), Venezuela (2010s) and Argentina (2010s - 2020s).

Weimar Germany (1922–23)

The period following World War I marked a pivotal chapter in German history, fraught with political and economic instability. In the aftermath of the war, Germany's economic condition was dire, exacerbated by enormous reparations demanded by the Treaty of Versailles, which placed an unbearable burden on the country. As the Weimar Republic grappled with these debts, it resorted to printing money to meet its obligations, triggering one of the most devastating instances of hyperinflation in history. By the end of 1923, the German economy had spiralled into chaos, with the mark rendered almost worthless, everyday goods becoming prohibitively expensive, and social fabric unravelling.

The Roots of Hyperinflation

To understand the catastrophic hyperinflation that ravaged Germany, we must first examine the conditions that led to it. The Treaty of Versailles, signed in 1919, placed the blame for World War I squarely on Germany’s shoulders. This resulted in a massive financial burden for the German state, which was required to pay reparations to the Allied powers. The reparations, which amounted to 132 billion gold marks (approximately $33 billion at the time), were payable in annual installments. Faced with such an enormous debt, the Weimar government struggled to find sufficient revenue through taxes.

To cover the gap, the government resorted to printing money. Initially, this may have seemed like a short-term solution to meet immediate obligations. However, as more marks flooded the economy, the value of the currency began to plummet. Excessive money supply coupled with stagnant goods production led to a rapid decline in the value of the mark. By 1922, Germany was caught in a vicious cycle: in an attempt to pay off its debts, it printed more money, leading to even greater inflation. As the price of goods escalated uncontrollably, confidence in the currency diminished rapidly.

The Acceleration of Inflation

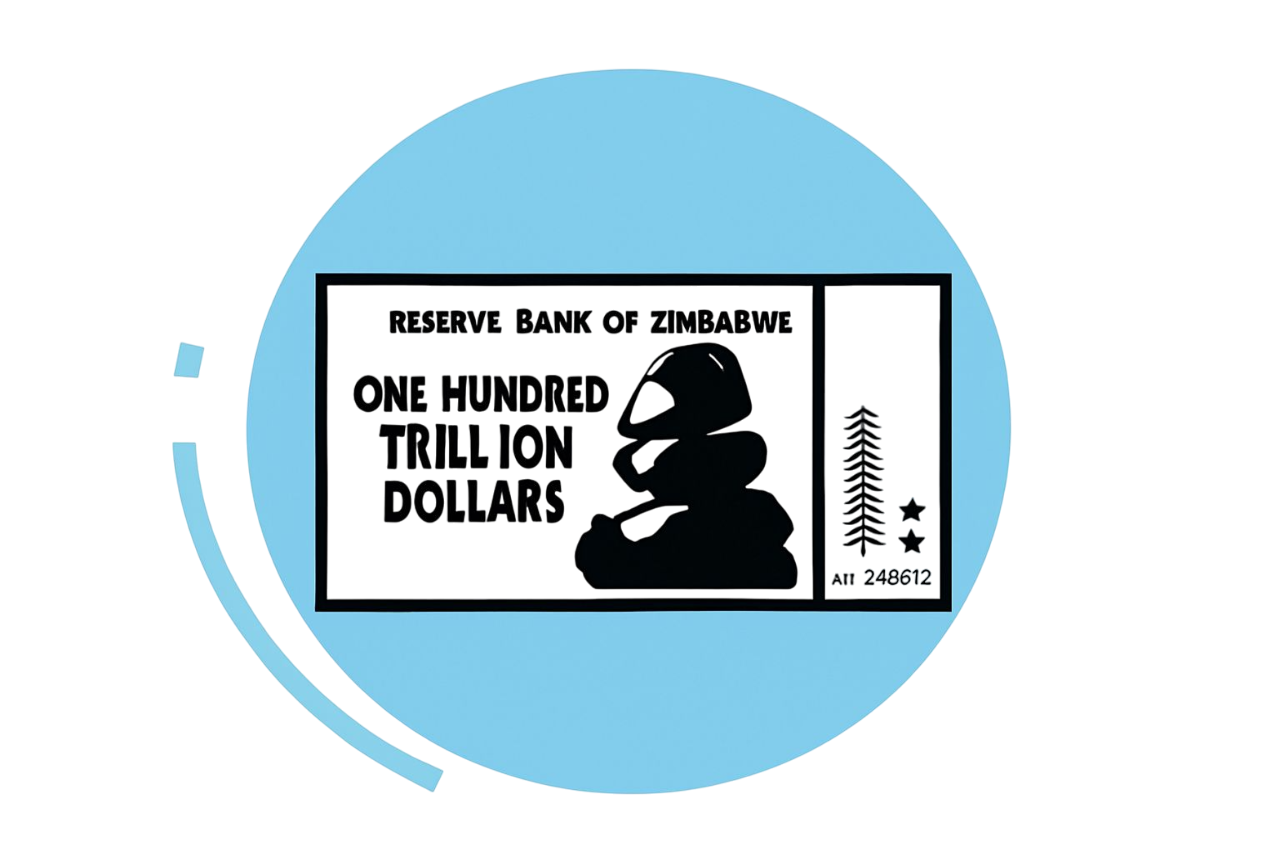

In the early stages of inflation, prices began to rise steadily. By July 1922, prices had already increased by 700% compared to the previous year. However, this was just the beginning. By 1923, the situation escalated into full-blown hyperinflation. The German mark’s value continued to collapse, driven by a combination of unsustainable money printing, political instability, and external pressures.

The events of 1923 are best illustrated by the staggering figures of the German economy at the time. By November 1923, one US dollar was worth one trillion marks. A loaf of bread that cost 160 marks in January 1923 would cost 200 billion marks by November. The rapid devaluation of the currency triggered a psychological shift in the population, where people began to distrust paper money entirely, opting instead to exchange goods directly or hoard tangible assets like real estate or foreign currency.

The Impact on Society

The effects of hyperinflation were felt across all sectors of German society, but none more acutely than the working class and the elderly. Pensioners saw their fixed incomes evaporate overnight, as their savings became worthless. Those who had worked hard throughout their lives found themselves destitute, unable to afford basic necessities like food. The plight of the middle and lower classes, particularly those on fixed incomes, is exemplified in the many heart-wrenching accounts of people being reduced to poverty almost overnight.

A famous example often cited in accounts of the Weimar hyperinflation involves a woman in Berlin who had a job working at a factory. She was paid once a week in marks, and on her way to the bank to cash her check, she would often watch the value of her wages erode before her very eyes. By the time she reached the bank, her wages were often worth less than when she had first received them.

The Wheelbarrow Phenomenon

Perhaps the most iconic image associated with Weimar hyperinflation is the sight of people carrying wheelbarrows filled with cash just to purchase basic goods. These images became symbolic of the complete breakdown of the currency system. In some instances, people would have to line up for hours to buy goods like bread or milk, only to find that by the time they reached the counter, the price had already risen. One particularly famous story tells of a man who ordered a coffee for 5,000 marks at a café, but when the coffee arrived, the price had risen to 7,000 marks.

The problem wasn’t just the rising prices; it was the complete unpredictability of the cost of everyday goods. People lost the ability to plan their finances, as the value of money was constantly in flux. The result was a total collapse of confidence in the currency, making it difficult for businesses to price goods or pay employees, and for consumers to afford anything at all.

Government Responses and the Introduction of the Rentenmark

In an attempt to halt the crisis, the German government undertook a series of measures. The most notable of these was the introduction of the Rentenmark in November 1923, a new currency that was backed by mortgages on industrial and agricultural assets. Unlike the mark, the Rentenmark was limited in supply, which helped restore some measure of stability to the economy. The Rentenmark was initially introduced alongside the continuing issuance of the old, devalued mark, but over time, the Rentenmark replaced the mark entirely.

While the Rentenmark helped stabilize the German economy in the short term, the damage to public trust was irreversible. Hyperinflation left deep scars on the German public's faith in the Weimar Republic's institutions, which many saw as weak and incapable of solving the country’s problems. It was during this period that extremist political movements, such as the Nazis, began to gain traction. The extreme discontent caused by economic instability, coupled with the resulting loss of confidence in the democratic system, provided fertile ground for the rise of radical ideologies.

Long-term Consequences and the Legacy of Weimar Hyperinflation

The legacy of the Weimar hyperinflation is profound. In the short term, it wreaked havoc on the German economy, decimating the middle class, undermining political stability, and causing widespread social unrest. Long-term, it contributed to a growing disillusionment with democratic institutions and a desire for strong, authoritarian leadership, which the Nazis capitalized on.

Historians and economists have long debated the precise role of the hyperinflation crisis in the eventual rise of Adolf Hitler. Many scholars argue that the trauma of hyperinflation, combined with the economic difficulties of the 1930s, created an environment in which extremist political ideologies could thrive, as people sought scapegoats and alternative solutions to their problems.

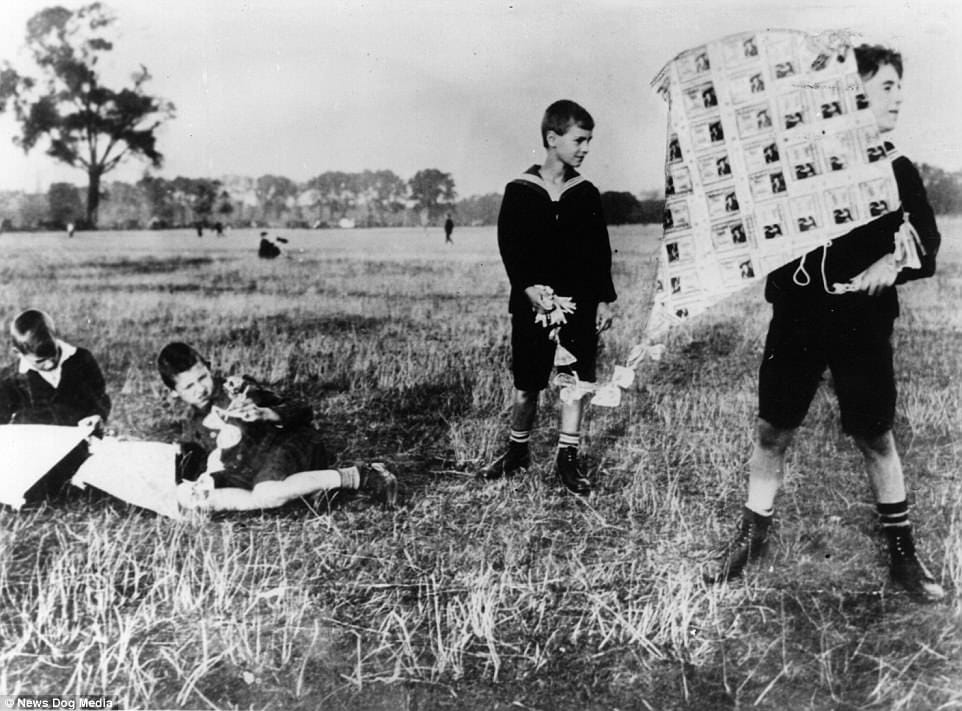

Visualizing the Weimar Hyperinflation

Conclusion

The Weimar hyperinflation of 1923 serves as a powerful reminder of the dangers of unchecked economic policies, particularly the risks associated with printing money to address financial crises. The collapse of the German mark and the widespread social upheaval it caused reshaped Germany’s political landscape, laying the groundwork for the rise of Nazi ideology. The episode is a stark illustration of how economic instability can lead to the erosion of public trust in government institutions, destabilizing not just the economy, but the very fabric of society itself. The Weimar hyperinflation remains one of the most dramatic cases in modern history of how extreme economic hardship can alter the course of history.

Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflation Crisis (2007–2009): Collapse of the “Breadbasket of Africa”

Between 2007 and 2009, Zimbabwe endured one of the most severe cases of hyperinflation in modern history. Echoing the experiences of Weimar Germany in the 1920s, the Zimbabwean crisis stemmed from a toxic mix of political decisions, economic mismanagement, and social upheaval. Within two years, the nation’s currency collapsed, wiping out savings, hollowing out the economy, and leaving millions impoverished. What makes Zimbabwe’s experience particularly significant is that it represents the first and only hyperinflationary episode of the 21st century, as noted by the World Bank, serving as a contemporary warning about the dangers of unsound economic governance.

Background: From Breadbasket to Breakdown

For much of the 20th century, Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia) was regarded as the “breadbasket of Africa” due to its fertile lands and strong agricultural sector, which supplied not only its own population but also neighboring countries. However, by the early 2000s, the country was in economic decline.

A major turning point came in 2000, when President Robert Mugabe’s government launched a controversial land reform program, seizing large-scale commercial farms (often owned by white Zimbabweans) and redistributing them. While intended to address long-standing colonial inequities, the policy was carried out chaotically, with farms handed to political allies who often lacked agricultural expertise or resources. This caused a sharp collapse in commercial farming, which had been the backbone of Zimbabwe’s export earnings, food supply, and foreign currency reserves.

Combined with political instability, corruption, and rising fiscal deficits, the land reform crisis set the stage for hyperinflation. By the mid-2000s, Zimbabwe was heavily reliant on imports, yet had little foreign currency to pay for them.

The Hyperinflationary Spiral

To cover widening budget deficits, the Zimbabwean government turned to the printing press, dramatically increasing the money supply without corresponding economic growth. The effects were devastating:

By 2007, inflation had already reached hundreds of percent per month.

By 2008, prices were doubling every few days. At its peak in November 2008, Zimbabwe’s inflation rate hit an estimated 79.6 billion percent month-on-month, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

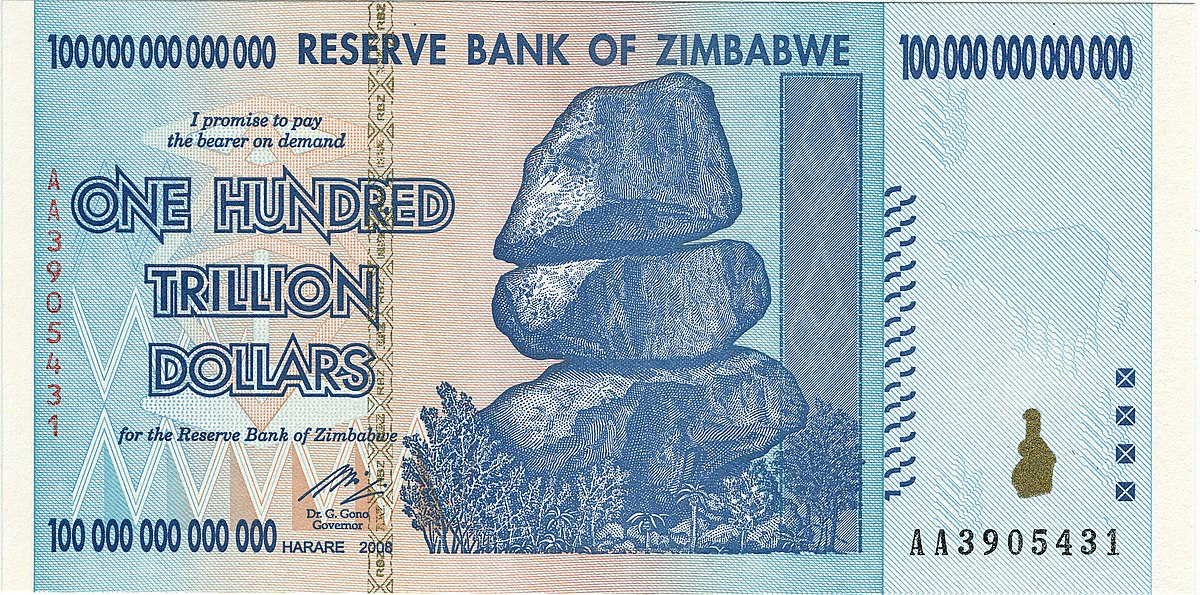

The Reserve Bank issued increasingly absurd denominations of banknotes: first millions, then billions, then trillions of Zimbabwean dollars. The largest note ever printed, issued in 2008, was for 100 trillion dollars—a now-infamous symbol of the country’s collapse.

Everyday life became surreal. People carried bags and wheelbarrows full of cash just to buy bread or bus fare. Employees demanded to be paid several times a day so they could rush to spend their wages before they became worthless. Shops ran out of goods as soon as they arrived, since consumers rushed to buy items as a hedge against the collapsing currency. In some cases, barter returned—with goods like cooking oil, sugar, or soap being traded in place of money.

Impact on Society

The social consequences of hyperinflation were catastrophic:

- Savings evaporated overnight. Ordinary Zimbabweans saw their bank accounts rendered meaningless, with decades of savings wiped out.

- Poverty skyrocketed. Once a middle-income country, Zimbabwe’s economy collapsed to the point where basic food security was no longer guaranteed. The World Food Programme estimated that by 2008, over half the population faced food shortages.

- Mass emigration occurred. Millions fled to neighboring countries—particularly South Africa, Botswana, and Mozambique—or further abroad. Those who stayed often survived on remittances from relatives overseas.

- Healthcare collapsed. Hospitals ran out of basic medicines, and life expectancy fell dramatically, exacerbated by the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Dollarization and the End of the Zimbabwe Dollar

By early 2009, Zimbabwe’s currency had become completely dysfunctional. In a desperate measure, the government abandoned the Zimbabwean dollar entirely and allowed transactions in foreign currencies, primarily the US dollar and the South African rand. This process, known as dollarization, effectively stabilized the economy by removing the government’s ability to print uncontrolled amounts of money.

Although stability returned, the damage was lasting. With no functioning domestic currency, Zimbabwe lost control over its monetary policy, and large parts of the economy became informal or dollar-based. Even after the introduction of new “Zimbabwean bond notes” in 2016, confidence in national currency remained deeply shaken.

Lessons and Historical Significance

Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation highlights the devastating impact of monetary irresponsibility combined with political turmoil. Like Weimar Germany, the crisis was not merely economic but deeply social and political, eroding trust in government institutions and creating lasting scars in national identity.

The crisis also illustrates the fragility of agricultural economies when mismanaged, especially in countries dependent on exports for foreign exchange. Furthermore, it underscores the role of governance: corruption, political violence, and authoritarian policies compounded economic problems that might otherwise have been contained.

For scholars and policymakers, Zimbabwe’s experience remains a crucial modern case study in how hyperinflation devastates societies, destroys institutions, and forces dramatic policy shifts.

Visualizing Zimbabwe’s Crisis

Conclusion

Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation of 2007–2009 stands as one of the starkest examples of economic collapse in living memory. From the breakdown of agriculture to the issuance of a 100 trillion dollar banknote, it represents not only a cautionary tale of policy failure but also a reminder of how swiftly prosperity can unravel. Much like Weimar Germany, the collapse of the currency was not just a financial disaster but a societal trauma, leaving deep scars that continue to shape Zimbabwe’s economy and politics today.

Venezuela’s Hyperinflation Crisis (2010s–2020s): Collapse of the Bolívar

Venezuela’s inflationary collapse stands as one of the most severe episodes of hyperinflation in the 21st century. While the country had long experienced cycles of instability, the crisis that unfolded in the 2010s was exceptional in its depth and duration. Rooted in economic mismanagement, dependence on oil revenues, and external shocks, Venezuela’s bolívar lost nearly all of its value. At its peak, annual inflation exceeded 80,000%, leaving salaries worthless within days and undermining all normal economic activity. The Venezuelan case is now frequently studied as a modern example of how fragile fiscal and monetary governance can destroy confidence in a national currency.

The Roots of the Crisis

Venezuela’s vulnerability stemmed from its over-reliance on oil exports, which accounted for over 90% of foreign exchange earnings. When global oil prices collapsed in 2014, the country’s revenues plunged. Instead of adjusting spending to match the decline in income, the government chose to finance large deficits through the printing of money by the central bank.

Compounding this problem were longstanding price and exchange controls, first introduced in the early 2000s. While designed to protect consumers, they discouraged domestic production, created widespread shortages, and pushed transactions into a growing black market. The combination of falling revenues, rigid economic controls, and excessive money creation set the stage for runaway inflation.

By the mid-2010s, inflation had already reached triple digits. In 2016, Venezuela officially entered hyperinflation, and conditions deteriorated rapidly:

- 2017–2018: Inflation accelerated to one of the highest rates ever recorded. The International Monetary Fund estimated annual inflation at 80,000% in 2018, with some projections placing it higher.

- Banknotes lost value almost instantly. A worker’s monthly wage often covered only a handful of basic goods, sometimes for just a few days.

- Shortages became widespread. Supermarket shelves emptied as imports became unaffordable and domestic production collapsed.

In response, the government issued ever-larger denominations of banknotes — first in thousands, then millions, and eventually in billions of bolívars. Yet these new notes quickly became obsolete as inflation surged ahead.

Currency Redenominations

To cope with the near-worthlessness of its money, Venezuela carried out multiple redenominations of its currency:

- 2008: The introduction of the bolívar fuerte (“strong bolívar”), cutting three zeros from the currency.

- 2018: Replacement with the bolívar soberano (“sovereign bolívar”), removing five more zeros.

- 2021: Another redenomination, slashing six additional zeros.

In total, 14 zeros were removed from the bolívar between 2008 and 2021. Yet each adjustment failed to solve the underlying problem of uncontrolled money creation and collapsing confidence.

The Social and Economic Costs

The inflationary collapse had devastating effects on Venezuelan society:

- Erosion of savings: Families lost decades of accumulated wealth as the currency evaporated.

- Falling real wages: Salaries, even when paid regularly, could not keep pace with prices.

- Rising poverty: According to UN data, by 2019 more than 90% of Venezuelans lived in poverty.

- Mass emigration: Over 7 million people fled the country by the early 2020s, creating one of the largest migration crises in the world.

For those who remained, day-to-day survival meant rushing to spend wages before prices increased, relying on barter, or depending on remittances from abroad.

Attempts at Stabilization

The Venezuelan government tried multiple strategies to rein in hyperinflation:

- Price and wage controls, often enforced by decree, which distorted markets further.

- Currency interventions, including redenominations and forced conversions.

- Partial dollarization, as the US dollar began to circulate unofficially in many transactions.

These measures, however, failed to restore lasting stability. Without structural reforms to fiscal policy and productive capacity, inflationary pressures persisted despite temporary slowdowns.

Lessons from Venezuela’s Hyperinflation

The Venezuelan experience illustrates several important lessons about modern inflationary crises:

- Resource dependence is a vulnerability. Economies heavily reliant on a single commodity—such as oil—face collapse when revenues fall and fiscal policy fails to adjust.

- Money printing is no substitute for reform. Financing deficits through central bank expansion undermines confidence in currency and can trigger uncontrollable inflation.

- Redenominations are cosmetic without credibility. Cutting zeros from the currency does not rebuild trust unless accompanied by real fiscal and institutional reforms.

- The social costs of inflation are profound. Beyond economics, hyperinflation erodes savings, destroys wages, fuels migration, and destabilizes political systems.

Visualizing Venezuela’s Crisis

Conclusion

Venezuela’s hyperinflation of the 2010s ranks among the most devastating monetary collapses in history. Unlike short-lived crises, it unfolded over years, grinding down household wealth and hollowing out the economy. Repeated redenominations of the bolívar, exchange controls, and emergency decrees could not mask the underlying reality: the collapse of fiscal discipline and productive capacity destroyed confidence in the national currency. Venezuela thus stands as a stark reminder of how economic mismanagement and reliance on the printing press can unravel even a resource-rich nation.

Argentina’s Inflationary Instability (2010s–2020s): A Persistent Currency Crisis

Argentina provides one of the most persistent and complex examples of inflationary instability in the modern era. Unlike Weimar Germany, Zimbabwe, or Venezuela—where hyperinflation appeared in acute bursts—Argentina’s problem has been one of persistence. Since the mid-20th century, the country has repeatedly cycled through inflationary episodes, debt defaults, and exchange-rate crises, with each recurrence linked to chronic fiscal imbalances, fragile institutions, and inconsistent economic policies.

While Argentina’s hyperinflation of the late 1980s and the collapse of the peso-dollar peg in 2001 remain dramatic historical milestones, the period from the 2010s into the 2020s demonstrates how unresolved structural weaknesses have kept the country locked in an inflationary trap.

Historical Roots of Inflationary Instability

The roots of Argentina’s inflation lie in a long-standing pattern of fiscal deficits financed by central bank money creation. Rather than relying on stable tax revenue or sustained borrowing, governments frequently turned to the printing press to cover budget shortfalls. Over decades, this eroded trust in the peso, encouraging Argentines to save and transact in US dollars whenever possible.

The Convertibility Plan of the 1990s, which pegged the peso one-to-one to the dollar, initially succeeded in breaking inflation. However, it came at the cost of economic rigidity: the fixed exchange rate limited Argentina’s ability to respond to external shocks. By the late 1990s, recession, rising debt, and capital flight made the peg unsustainable, culminating in the dramatic collapse of 2001–2002. The country defaulted on its debt, banks froze deposits, and the peso lost about 70% of its value within months. Though inflation was contained after the crisis, it never fully disappeared, and structural weaknesses persisted.

The 2010s–2020s Crisis

By the 2010s, Argentina was once again entrenched in high inflation. Governments alternated between orthodox and heterodox strategies—some focusing on fiscal tightening and negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), others relying on subsidies, wage-price agreements, and strict currency controls. Yet none provided a lasting solution.

Key features of this period include:

- Persistent fiscal deficits: Successive administrations were unable or unwilling to reduce public spending sufficiently. When borrowing became difficult, the central bank resumed printing money to finance the deficit.

- Accelerating inflation: Already high at the beginning of the decade, inflation steadily increased. By 2022, annual inflation exceeded 100%, and through 2023–2025 Argentina consistently ranked among the world’s highest-inflation economies.

- Peso depreciation: The peso weakened drastically in both official and parallel (black-market) exchange markets. Frequent devaluations, rather than restoring competitiveness, deepened instability as households and businesses rushed to convert pesos into dollars at the first sign of trouble.

- Exchange controls and distortions: Scarcity of dollars forced the government to impose tight foreign-exchange controls. These measures restricted imports, distorted trade and investment decisions, and encouraged the growth of a thriving parallel currency market.

The crisis had a self-reinforcing dynamic: weak fiscal discipline led to money printing, which fuelled inflation, which in turn undermined the peso. Each attempt to stabilize the situation—whether through IMF agreements or short-lived exchange-rate strategies—collapsed under the weight of unresolved fiscal imbalances and political resistance to structural reform.

Social and Economic Consequences

The prolonged inflationary crisis has exacted steep costs:

- Erosion of real wages: As prices outpaced incomes, purchasing power stagnated or declined for much of the population.

- Rising poverty: By the early 2020s, poverty levels increased sharply, with food insecurity affecting millions.

- Investment collapse: Chronic uncertainty over exchange rates, inflation, and debt repayment discouraged both domestic and foreign investment.

- Dollar dependence: With little confidence in the peso, Argentines increasingly used the dollar for savings, property transactions, and even day-to-day purchases, deepening the economy’s reliance on a foreign currency it struggled to earn.

Policy Lessons from Argentina

Argentina’s experience underscores several key lessons about inflation and currency crises:

- Fiscal foundations matter most. Monetary reform, such as exchange-rate pegs or price agreements, cannot succeed unless supported by credible fiscal policy. Without a fiscal anchor, inflationary pressures inevitably re-emerge.

- Exchange-rate pegs are fragile. While pegging the peso to the dollar in the 1990s temporarily stabilized prices, it ultimately collapsed because it was not accompanied by structural reforms and fiscal discipline.

- Credibility is hard to restore. Once confidence in a currency is lost, it cannot be regained through quick fixes. Restoring trust requires consistent, transparent, and sustained policies over many years — something Argentina has historically failed to achieve.

- Dollarization culture is self-perpetuating. In an economy where households and firms habitually turn to the dollar as a store of value, the central bank’s ability to conduct independent monetary policy becomes severely constrained.

Visualizing Argentina’s Crisis

Conclusion

Argentina’s prolonged battle with inflation illustrates the challenges of restoring monetary stability in a country where fiscal weakness, political divisions, and institutional fragility persist. Unlike the short-lived but extreme hyperinflations of Weimar Germany or Zimbabwe, Argentina’s crisis has unfolded over decades, eroding confidence gradually but relentlessly. The story of Argentina’s inflation is thus less about a single moment of collapse and more about a cycle of instability, in which temporary reforms give way to recurring crises. It serves as a reminder that monetary stability cannot be achieved without credible fiscal discipline, political consensus, and strong institutions.

Robust Policy and Analytical Takeaways

Taken together, the experiences of Weimar Germany, Zimbabwe, Venezuela, and Argentina demonstrate the destructive power of inflationary and currency crises across very different historical and political contexts. Despite unique circumstances—war reparations in Weimar, chaotic land reform in Zimbabwe, oil dependence and sanctions in Venezuela, and chronic fiscal weakness in Argentina—each case underscores a common pattern: when governments rely on money creation to cover deficits without credible fiscal discipline, public confidence in currency collapses.

The consequences are severe and consistent: savings are wiped out, real wages fall, poverty rises, and social trust erodes. Political stability often suffers as well, creating openings for unrest or authoritarian responses. Temporary measures such as redenominations, exchange-rate pegs, or price controls may provide short-lived relief, but without structural reform and credible fiscal anchors, inflationary spirals return.

The central lesson across a century of crises is clear: currency stability depends not only on monetary policy but also on sound fiscal management, strong institutions, and sustained credibility. Once trust in money is lost, it is extraordinarily difficult to regain—making prevention far less costly than recovery.

By looking at real-world economic crises and currency failures, we’ve seen how vulnerabilities in traditional monetary systems can have widespread consequences. These case studies highlight the growing need for more resilient, inclusive, and adaptive financial infrastructure. In the next lesson, The Digital Age and Traditional Finance, we’ll explore how technology is reshaping conventional finance—examining both the advancements it has enabled and the limitations that still persist in today’s digital financial landscape.