1.6 The Dawn of a New Era: Cryptocurrency as a Solution

After exploring money’s problems, we can see why cryptocurrency emerged in the late 2000s. Its creation was a direct response to issues of centralisation, inflation, and inefficiency.

The 2008 Financial Crisis and the Collapse of Trust

The 2007–2008 Global Financial Crisis was one of the most significant economic shocks since the Great Depression. It was triggered by risky bank lending, collapsing housing markets, and toxic assets. On Sept 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers, then the fourth-largest investment bank in the United States, filed for bankruptcy after 158 years of operation. This event sent panic through the global economy, wiping out trillions in wealth, freezing credit markets, and triggering government interventions of unprecedented scale.

Governments injected billions to bail out failing banks—actions that underscored the degree to which modern economies depend on centralized institutions and taxpayer-funded safety nets. The crisis highlighted two uncomfortable truths:

- Concentration of Power: A handful of global banks controlled the stability of the system.

- Fragility of Trust: Once faith in institutions falters, panic spreads quickly, forcing governments to act as backstops.

“The financial crisis showed how interlinked the global economy had become—and how fragile those links were.”

— Ben Bernanke, former Federal Reserve Chair (2015 lecture series, Princeton University)

For millions of ordinary people, the crisis translated into job losses, foreclosures, frozen credit, and falling savings. It also prompted a philosophical question: should money and payments rely so heavily on trusted intermediaries?

Confidence in the financial system plummeted, highlighting a need for a payment system outside traditional institutions.

"The collapse of Lehman Brothers became the signal event of the 2008 financial crisis"

The Genesis of Bitcoin

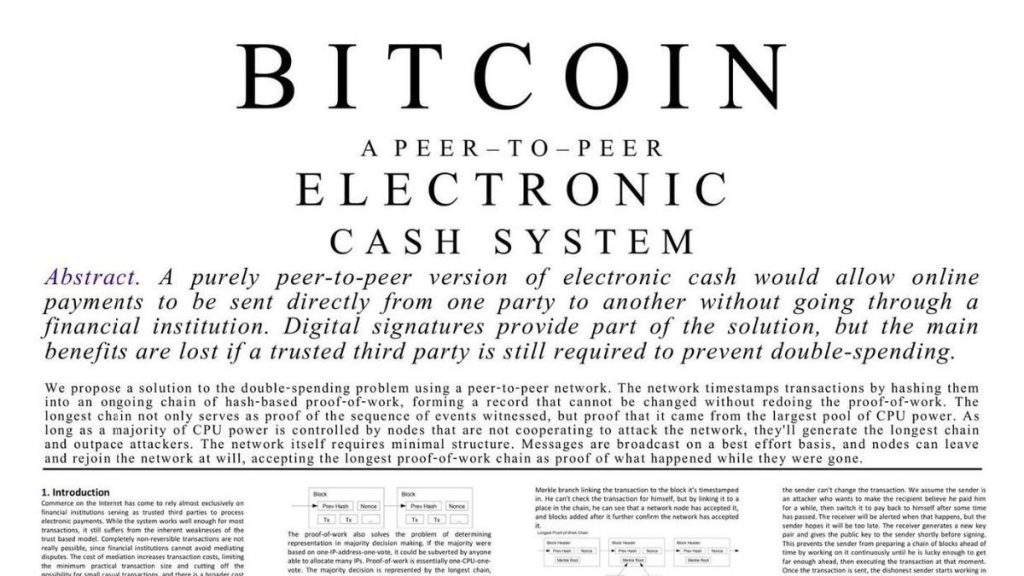

In this climate, an anonymous developer (or group) calling themselves Satoshi Nakamoto proposed a radically different model for money. On October 31, 2008, Satoshi published the Bitcoin white paper, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System,” to a small cryptography mailing list.

The proposal was striking in its simplicity: a digital currency system that would allow value to be transferred “peer-to-peer, with no trusted third-party”. In other words, it aimed to eliminate banks and middlemen: transactions would be direct between users, secured by cryptography.

On January 3, 2009, Bitcoin officially launched when Nakamoto mined the genesis block of the Bitcoin blockchain. Notably, embedded in this block was a line from The Times newspaper: “Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks”. This hidden message served as a timestamp and a commentary on the broken banking system that Bitcoin set out to improve. In effect, Bitcoin was framed as a protest against the old system. Its public ledger (blockchain) would record transactions in a way that no single party could alter. As one crypto writer noted, Satoshi’s white paper “laid out an inspiring new definition of money at a time when faith in the traditional financial system was still being salvaged”.

An introduction to Bitcoin’s origins, design, and significance

“What is needed is an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust.”

— Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin white paper (2008)

By the early 2010s, Bitcoin was a fringe experiment—but one that resonated across diverse groups:

- Technologists admired its elegant solution to double spending.

- Libertarians celebrated its independence from governments.

- Investors saw a new asset class with asymmetric upside.

- Developing economies saw potential in bypassing weak banks and unstable currencies.

“Bitcoin is more than just a currency. It is a new way of thinking about money.” — The Economist

What are Cryptocurrencies?

Cryptocurrencies are digital currencies designed to overcome the numerous flaws, and cumbersome aspects of traditional finance. They are seen by many as the new financial frontier with solid foundations in decentralization, typically operating on a technology called blockchain (a digital ledger enforced by a network of computers called nodes). They are secured using cryptography, which ensures that transactions are secure and that only the sender and recipient can access the information.

Cryptocurrencies are still evolving, but their core promise is clear: use math and consensus to make money that is transparent, secure, and not subject to one party’s whims. This solves the “trust issue” that fiat systems suffer from. As Satoshi wrote, instead of trusting banks, the system uses cryptography, so that “completely non-reversible transactions” become possible without intermediaries.

Key Features: Decentralization and Trustlessness

How does cryptocurrency address the problems we saw? The core idea is decentralization. In Bitcoin and similar systems, the rules are encoded in transparent software. There is a fixed supply (e.g. 21 million bitcoins) that no one can unilaterally inflate. Transactions are recorded on a public ledger maintained by a network of computers around the world. This means: no single authority can freeze your funds or suddenly change the currency policy. If a government bans bitcoin in one country, people elsewhere can still transact.

Moreover, cryptocurrency uses cryptographic proof instead of trust. Instead of trusting a bank to confirm you paid someone, the network agrees by solving math puzzles (mining) and validating a block of transactions. Once confirmed, a transfer is permanent and cannot be reversed by a third party. (In contrast, a credit card payment can be reversed by a chargeback, and a bank account can be seized on orders from authorities.) In Bitcoin’s design, nobody can create new coins beyond the agreed limit, so long-term predictability is built in. Users hold private keys (like secret passwords) that only they know, so only they can authorise spending their coins.

Early adopters around the world tested these ideas. Enthusiasts saw crypto as “censorship-resistant money”: if a government froze banks, Bitcoin wallets would stay liquid. (For instance, a few people in Cyprus 2013 did use Bitcoin to move funds when banks imposed limits.) In places with cash crises (Argentina, Brazil, Greece), some started buying Bitcoin or local crypto tokens to preserve value or make cross-border payments without banking delays. Of course, Bitcoin and its siblings came with new challenges (such as price volatility and the need to manage private keys), but the core promise was clear: a form of money designed to sidestep the failures of the old system.

A clear explanation of the mathematical foundations of Bitcoin and blockchain technology

Early Adoption and Global Reach

By the 2010s, thousands of people and businesses globally were experimenting with cryptocurrency. Online forums, meetups, and conferences sprang up. Merchants who once faced 3–4% credit card fees began accepting Bitcoin for novelty (and sometimes to attract tech-savvy customers). Remittance services started using crypto rails to lower fees (as seen in Venezuela and elsewhere). Bold investors heralded crypto as the future of finance.

At the same time, sceptics raised concerns: crypto prices could crash, and criminals might exploit anonymity. Yet each technological wave in history has its doubters. Today, interest is broadening beyond Bitcoin to many other cryptocurrencies and blockchain applications. Importantly for our course, cryptocurrency is not just about new “coins”—it introduces a new model of money. It puts individuals more directly in control of their funds (without intermediaries) and uses math and code as enforcement rather than trust in institutions.

In this lesson, we explored how cryptocurrencies emerged as a response to the limitations of traditional financial systems—offering decentralized, transparent, and borderless alternatives to conventional money. But to truly understand the impact of this shift, it’s important to clarify what sets cryptocurrencies apart from the forms of money we already use. In the next lesson, Fiat Money, Digital Currencies and Cryptocurrencies: A Comprehensive Overview, we’ll break down the key characteristics of each, helping you understand how they compare, how they coexist, and why these distinctions matter in today’s evolving financial landscape.